Scott and Mark Kelly, twins that look almost exactly the same inside and out, make them the ideal subjects to check and compare their bodies to the contrasts of living in different environments.

NASA took the opportunity to study the effects of what space travel would do to a human body – so they tried the experiment on one twin being up in space, while the other being down on Earth, living like a normal person in their natural environment.

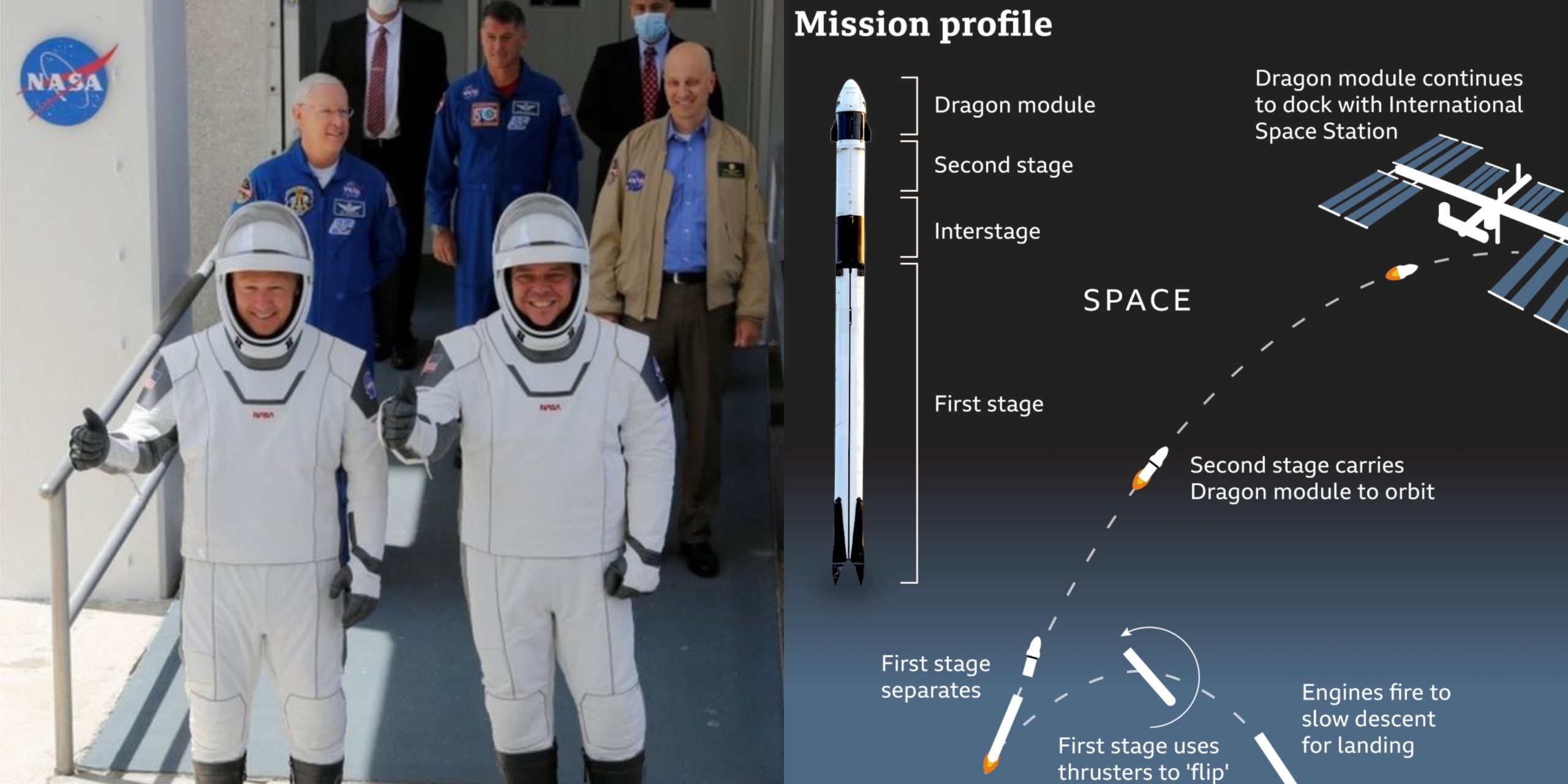

Scott Kelly was to stay up in the International Space Station for one year, living like an astronaut in the presence of little to no gravity. The experiment lasted one year, from March 27, 2015, to March 2, 2016. Throughout Scott’s journey, scientists would study the twins and compare them from molecular, psychological, and behavioral angles to spot any change in them.

The findings, published in April 2019 in a journal would give insight if we would one day travel to Mars or beyond. According to the journal;

Scott’s overall health was optimal during his stay, but scientists did notice a few small changes in his body.

The ends of Scott’s chromosomes, known as telomeres, seem to elongate, but they aren’t sure of what effects it could happen on him.

The difference involves the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, known as telomeres. These bits of genetic material are biomarkers of aging and potential health risk, says study coauthor Susan Bailey, a health researcher at Colorado State University.

While aboard the ISS, Scott’s telomeres became elongated, although it’s hard to know at this stage what, if any, effects that might have.

Researchers also found abnormalities such as inversions and translocations in some of Scott’s chromosomes and some damage to his DNA, as well as changes in his gene expression. Beyond these genetic effects, Scott developed thickening in his retina and in his carotid artery.

There were also shifts in Scott’s gut microbiome that differed from those of his Earth-bound twin.

Upon his return, more than 90 percent of Scott’s genes returned to normal expression levels, but some small changes persisted. And while most of his elongated telomeres quickly returned to typical length upon return, some became even shorter than they were pre-flight. This shortening may be a concern that merits further study in other astronauts, Bailey says in an email, “because short telomeres have been associated with reduced fertility” along with dementia, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers.

Still, this does not necessarily prove anything yet, cautions Carol Greider, a Nobel prize-winning molecular biologist who was not involved with the study. “We do not know the telomere length correlation and fluctuations of twins on Earth,” she writes in an email, “so there is no expectation of what might be found.”

Some chromosomal inversions also persisted, Bailey says, “and so could contribute to genomic instability, which could increase risk of developing cancer.” In the months after Scott returned, researchers also noticed a persistent reduction in his cognitive skills.

“It wasn’t getting worse, but it also was not getting any better,” says study coauthor Matthias Basner of the University of Pennsylvania’s department of sleep and psychiatry.

Does that mean that staying in space for a year makes you sick and less smart?

Definitely not. First of all, the entire research team emphasizes the shortcomings of this study’s extremely small sample size.

“The big caveat is that this is only an n equals one,” Basner says, referring to the shorthand scientists use to represent the number of samples or participants in a study. “If you count Mark, it’s at best n equals two.” Without studying many more test subjects, it’s impossible to know for sure whether these effects on Scott’s health are specific to his particular physiology or generally representative of most people under similar conditions.

“Any persistent changes were very small and would need to be replicated in additional astronauts before attributing them to spaceflight, or even differences from normal variation,” says study coauthor Andy Feinberg of Johns Hopkins University.

Though, this study does not determine definitively what true space travel would do to the human body, since the ISS is still influenced in our planet’s magnetic field, not like the deep space that’s far from the range of our planet where it’s not protected from harmful cosmic radiation.

Also, the limited supply of Scott’s blood also makes it hard to get a thorough study of the effects of space travel, since the sample would need to travel back to Earth – landing in Russia to be transported to labs all around the world.

Scott also could not be giving more blood than usual, because it was for “his own safety”.

NASA is planning to do more studies like this by sending astronauts off beyond low-Earth orbits, like the moon, or even further.

In the near future, NASA hopes that they would be able to equip the astronauts with the ability to go through such a daring act.

Source: National Geographic, Wired

Leave a Comment