Our Earth is getting old. According to National Geographic, the age of the earth is estimated to be about 50 million years. It might be beyond that as human research can be very limited to study our most wonderful universe.

Even a man can have a lot of health problems when in reach of older age, the same goes for our beloved earth. 2020 has become the year where the world is facing a global threat. The coronavirus pandemic that started at the end of 2019, has spread all across the world and had affected everything. Another biggest threat that happened globally is climate change.

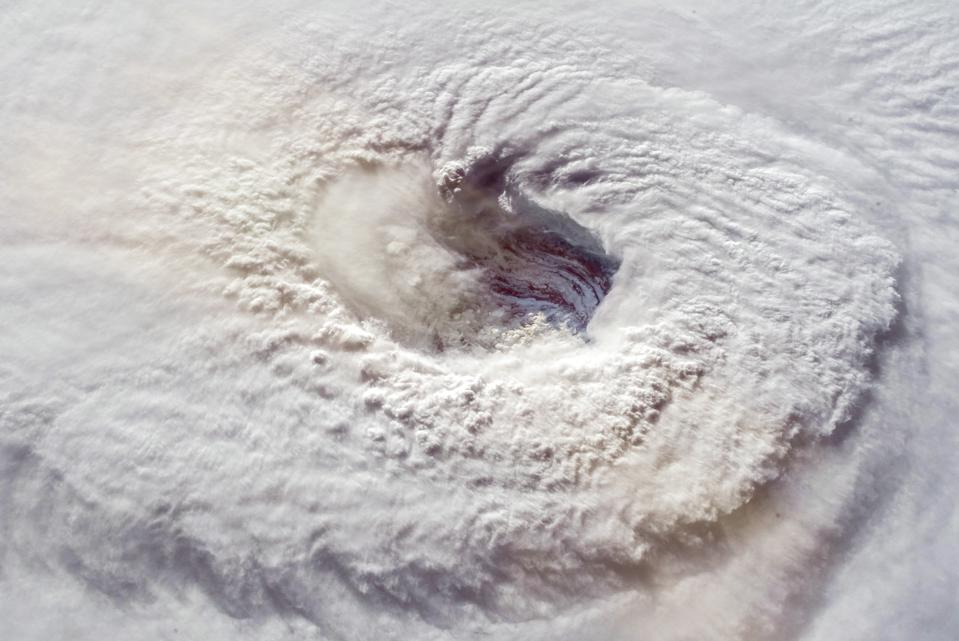

To add to our concerns, a meteorologist, Phil Klotzbach forecasted an active hurricane season in the Atlantic. It is predicted to be an active and destructive hurricane season.

Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predict around 13 to 19 large storms could spin up this year. This could lead to as many as six becoming major hurricanes. Another four major hurricanes were predicted by the Colorado State University. The major hurricanes which are in Category 3 or higher with winds surpassing 111 miles per hour.

Last month, South Texas was flooded with water due to Hurricane Hanna.

Hurricanes can be easily influenced by climatic conditions. Warm sea surface temperature can be the fuel that leads up to a hurricane. Hurricane Dorian that happened last year in the Bahamas was the result of warm September waters in the Caribbean Sea.

Forecasters also closely monitor the weather cycle called the El Nino Southern Oscillation. El Nino is associated with warm, wet precipitation in the western U.S and eastern Pacific. This weather can increase the risk for the Atlantic hurricane season to happen.

Besides that, The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration is responsible for operational hurricane forecasting and monitoring in the United States. NASA’s role as a research agency is to develop new types of observational capabilities and analytical tools to learn about the fundamental processes that drive hurricanes and the connections between hurricanes and regional rainfall variability to incorporate data that capture those mechanisms in forecasts.

“The fire season forecast is consistent with what we saw in 2005 and 2010 when warm Atlantic sea surface temperatures spawned a series of severe hurricanes and triggered record droughts across the southern Amazon that culminated in widespread Amazon forest fires,” said Doug Morton, chief of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Morton is co-creator of an Amazon fire seasonforecast. Now in its ninth year, the forecast analyzes the relationship between climate conditions and active fire detections from NASA satellite instruments, such as the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on Terra and Aqua, to predict fire season severity.

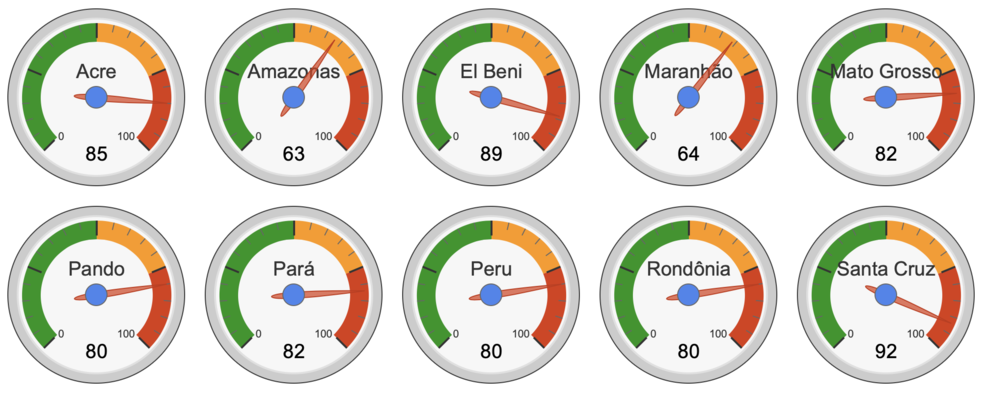

“Our seasonal fire forecast provides an early indication of fire risk to guide preparations across the region,” Morton said, noting that the forecast is most accurate three months before the peak of burning in the southern Amazon in September. “Now, satellite-based estimates of active fires and rainfall will be the best guide to how the 2020 fire season unfolds.”

This Amazon fire season is one to watch with yet extra caution, Morton said. The Brazilian states with the highest projected fire risk this season — Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia — were among the regions with the most deforestation fire activity last year, which itself saw the largest number of active fire detections in the Amazon basin since 2010.

The long-term outlook for the Amazon fire season is dependent on both climate and human fire ignitions, said Yang Chen, Earth scientist at the University of California, Irvine, and co-creator of the Amazon fire season forecast.

“Changes in human fire use, specifically deforestation, add more year-to-year variability in Amazon fires,” Chen said. “In addition, climate change is likely to make the entire region drier and more flammable – conditions that would allow fires for deforestation or agricultural use to spread into standing Amazon forests.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. Atlantic hurricane season has already shown signs of increased activity, with five named storms already in the books early in the season, Morton said. Nevertheless, a complex set of conditions influence the formation of tropical storms. For instance, in June, a large Saharan dust plume wafted across the Atlantic, temporarily suppressing storm formation. These circumstances highlight both the interconnectedness and complexity of the Earth system, as rapid changes in atmospheric conditions or sea surface temperatures will influence rainfall patterns in 2020 and the potential for synchronized impacts from hurricanes and fires.

Source: NASA, National Geographic

Leave a Comment